Country Wide Magazine, August 2022

Planting 10% of a farm in trees has extra benefits with little loss of production. Annabelle Latz reports.

Retiring livestock farming on a small portion of a North Canterbury hill farm and putting it into trees would result in very little drop in production, a forestry advocate says. Alistair adds there would be the extra benefit of claiming carbon credits.

“It surprises me that not more farmers are seeing it, changing even just 10 to 20% of the land use.”

He said young farmers were starting to look at their budgets and do it. The former fruit grower said farmers have a choice of why to grow trees, whether that be for carbon credits or timber, and the end reason can change, depending on the market. The 72-year-old retiree describes it as a coincidence that his hobby and interest came up trumps because of the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS), and said his venture with eucalyptus trees is one decision he is certain of. Alistair was the first chairman of New Zealand Summer Fruit Export Council and the 2021 South Island Farm Forester of the year. He left behind an extensive and comprehensive career in fruit growing on the northern fringe of Christchurch nine years ago for retirement. He and his wife bought 63 hectares of bare land in Glenmark, North Canterbury to pursue Alistair’s long interest in forestry, which he’d followed for some 40 years after a course through Wellington Open Polytechnic.

Upon arrival at Glenmark, they logged two thirds of the Indian cedars that were there, and built their house. Nearly a decade ago under the ETS, NZ carbon units were only $3 to $4 per tonne, so Alistair’s initial thought was to plant the property in radiata pine, adding to the 6ha already in the ground. In the following years, their value leapt to $15/tonne.

About three years ago things started to change again, when unit prices hit better than $25/tonne, and a year ago unit prices hit $35/tonne. “At that rate, you’d be best to keep them growing rather than harvesting, they’ll have significant tonnages to 100 years old.” The retirement venture has certainly kept them busy. They farm 100 composite ewes which they breed from with a Texel ram.

Focus on trees

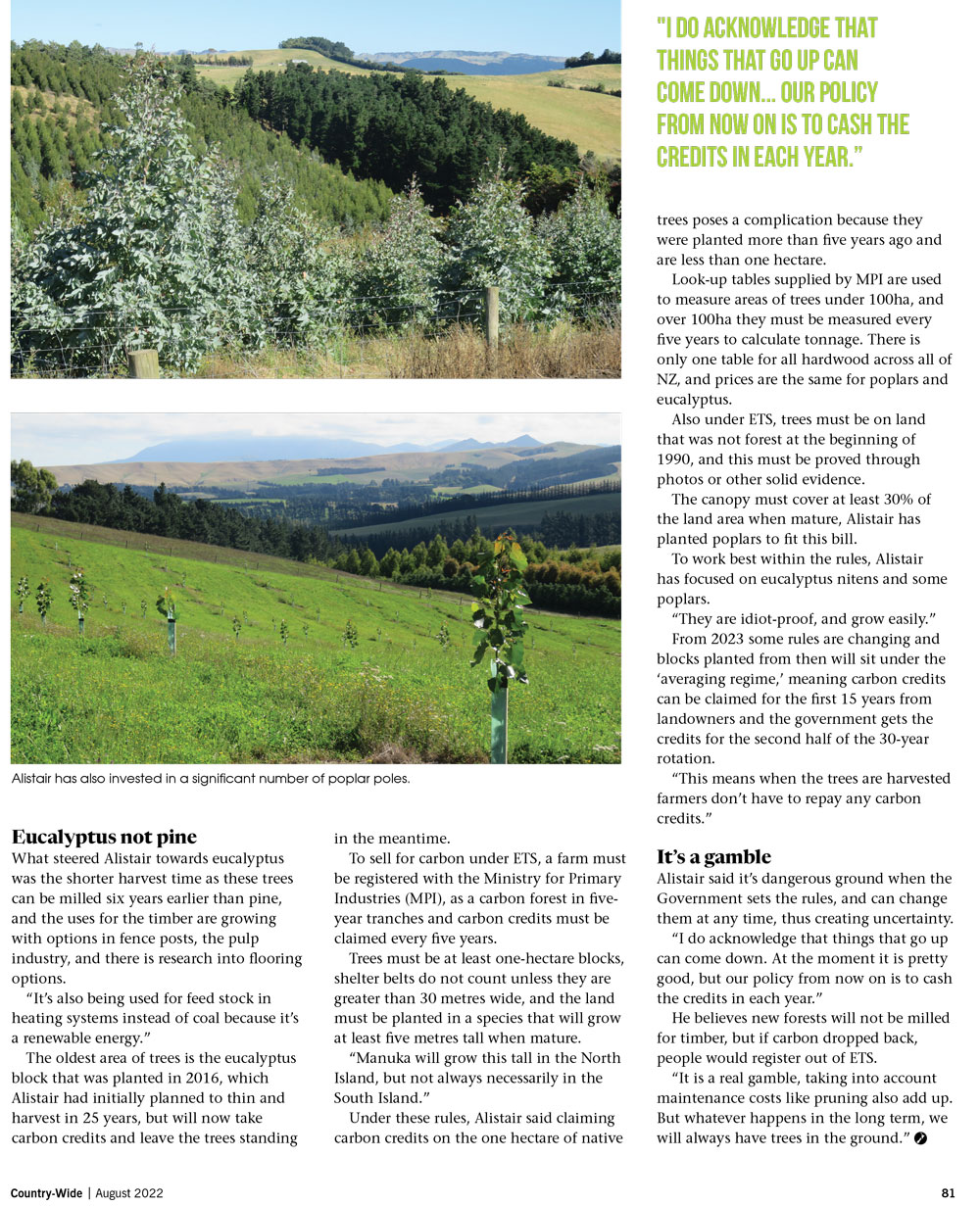

For the tree side of the operation, they have planted most of land in eucalyptus totaling 44ha, one hectare of beech and kauri, half a hectare of totara, five hectares of poplars, one hectare of redwoods, and two hectares of Douglas fir. In addition, they have a hectare of native plantings in two different blocks. “It has cost $2000/ha to plant eucalyptus, which includes the trees, pre-planting and post planting spray. Poplar poles are the much cheaper option, as I cut my own poles.” The carbon unit price is $76/tonne for any tree whether that be pine or hardwood and Alistair admits the Minister for Climate Change would be comfortable to see prices above $100/tonne.

“I don’t see much downside for the carbon price, unless a world war or something like that. While ETS is at a high price, I won’t be logging them.” “I do acknowledge that things that go up can come down… our policy from now on is to cash the credits in each year.”

Eucalyptus not pine

What steered Alistair towards eucalyptus was the shorter harvest time as these trees can be milled six years earlier than pine, and the uses for the timber are growing with options in fence posts, the pulp industry, and there is research into flooring options.

“It’s also being used for feed stock in heating systems instead of coal because it’s a renewable energy.”

The oldest area of trees is the eucalyptus block that was planted in 2016, which Alistair had initially planned to thin and harvest in 25 years, but will now take carbon credits and leave the trees standing in the meantime. To sell for carbon under ETS, a farm must be registered with the Ministry for Primary Industries (MPI), as a carbon forest in five- year tranches and carbon credits must be claimed every five years. Trees must be at least one-hectare blocks, shelter belts do not count unless they are greater than 30 metres wide, and the land must be planted in a species that will grow at least five metres tall when mature.

“Manuka will grow this tall in the North Island, but not always necessarily in the South Island.”

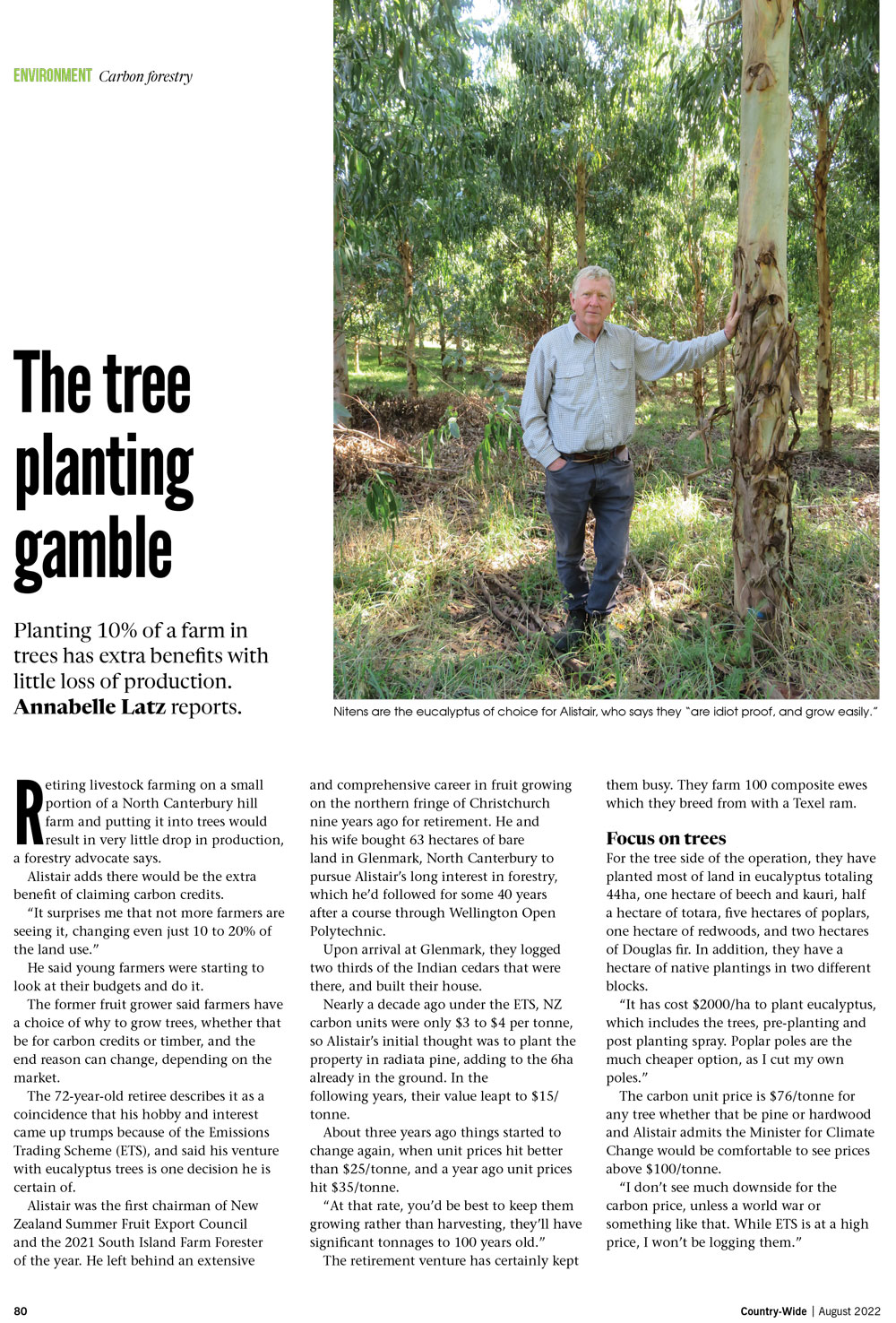

Under these rules, Alistair said claiming carbon credits on the one hectare of native trees poses a complication because they were planted more than five years ago and are less than one hectare. Look-up tables supplied by MPI are used to measure areas of trees under 100ha, and over 100ha they must be measured every five years to calculate tonnage. There is only one table for all hardwood across all of NZ, and prices are the same for poplars and eucalyptus. Also under ETS, trees must be on land that was not forest at the beginning of 1990, and this must be proved through photos or other solid evidence. The canopy must cover at least 30% of the land area when mature, Alistair has planted poplars to fit this bill. To work best within the rules, Alistair has focused on eucalyptus nitens and some poplars.

“They are idiot-proof, and grow easily.”

From 2023 some rules are changing and blocks planted from then will sit under the ‘averaging regime,’ meaning carbon credits can be claimed for the first 15 years from landowners and the government gets the credits for the second half of the 30-year rotation.

“This means when the trees are harvested farmers don’t have to repay any carbon credits.”

It’s a gamble

Alistair said it’s dangerous ground when the Government sets the rules, and can change them at any time, thus creating uncertainty. “I do acknowledge that things that go up can come down. At the moment it is pretty good, but our policy from now on is to cash the credits in each year.” He believes new forests will not be milled for timber, but if carbon dropped back, people would register out of ETS. “It is a real gamble, taking into account maintenance costs like pruning also add up. But whatever happens in the long term, we will always have trees in the ground.”

See the article online here