Finding the balance, New Zealand

Country Wide Magazine, November 2021.

Strict crop rotation is a key to success for the Bierema family on their Mid Canterbury farm, Annabelle Latz writes.

Running a successful cropping farm is about being consistently good, not always striving for records. Steven and Freda Bierema along with their three young sons moved on to their Mid Canterbury farm in the winter of 2004, from the Netherlands. It was a case of seeing how the arable farming Kiwis do it and following suit, while they found their feet.

Two adults, three young boys, seven suitcases.

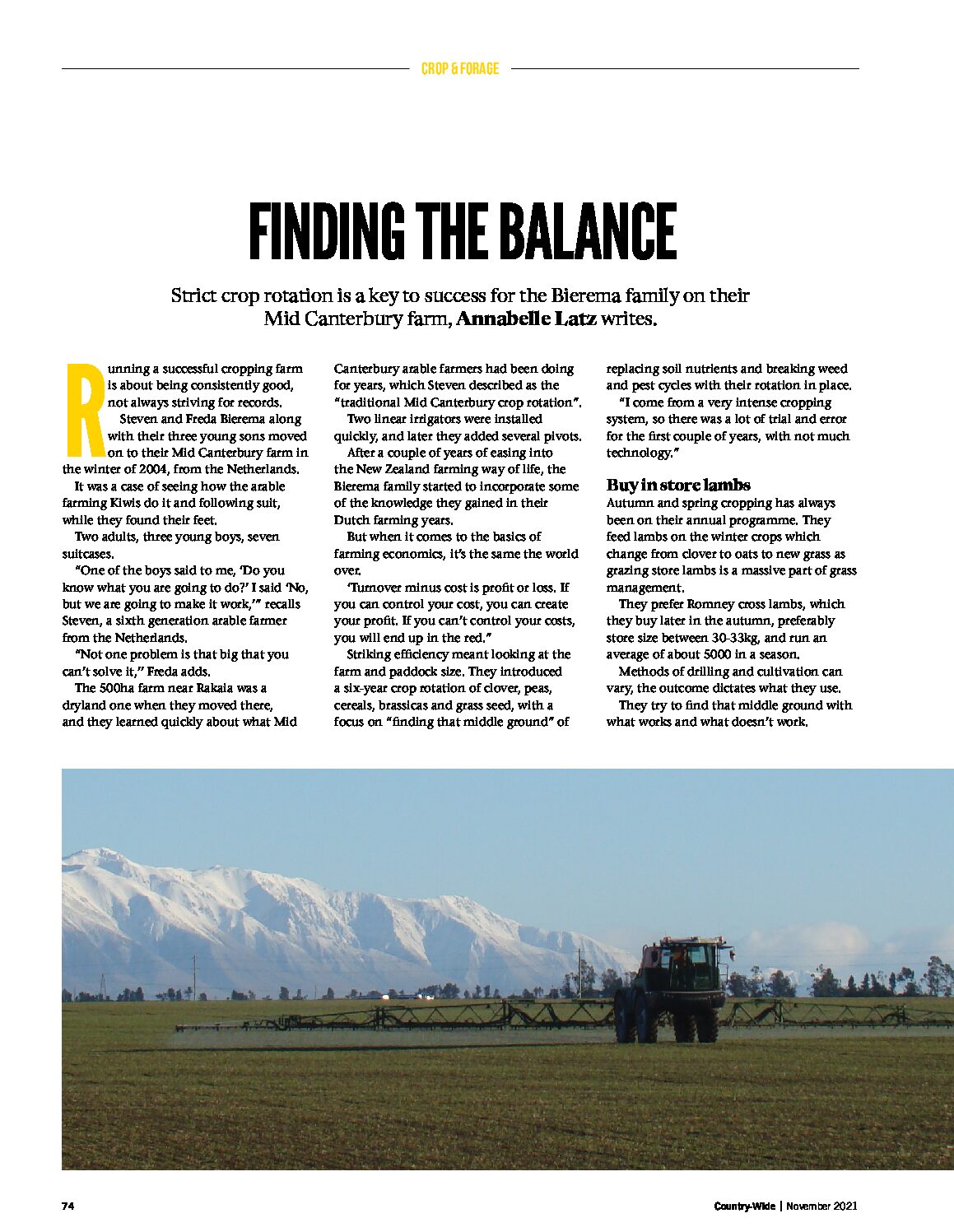

“One of the boys said to me, ‘Do you know what you are going to do?’ I said ‘No, but we are going to make it work,’” recalls Steven, a sixth generation arable farmer from the Netherlands. “Not one problem is that big that you can’t solve it,’’ Freda adds. The 500ha farm near Rakaia was a dryland one when they moved there, and they learned quickly about what Mid Canterbury arable farmers had been doing for years, which Steven described as the “traditional Mid Canterbury crop rotation”. Two linear irrigators were installed quickly, and later they added several pivots. After a couple of years of easing into the New Zealand farming way of life, the Bierema family started to incorporate some of the knowledge they gained in their Dutch farming years.

But when it comes to the basics of farming economics, it’s the same the world over.

‘Turnover minus cost is profit or loss. If you can control your cost, you can create your profit. If you can’t control your costs, you will end up in the red.” Striking efficiency meant looking at the farm and paddock size. They introduced a six-year crop rotation of clover, peas, cereals, brassicas and grass seed, with a focus on “finding that middle ground” of replacing soil nutrients and breaking weed and pest cycles with their rotation in place.

“I come from a very intense cropping system, so there was a lot of trial and error for the first couple of years, with not much technology.”

Buy in store lambs

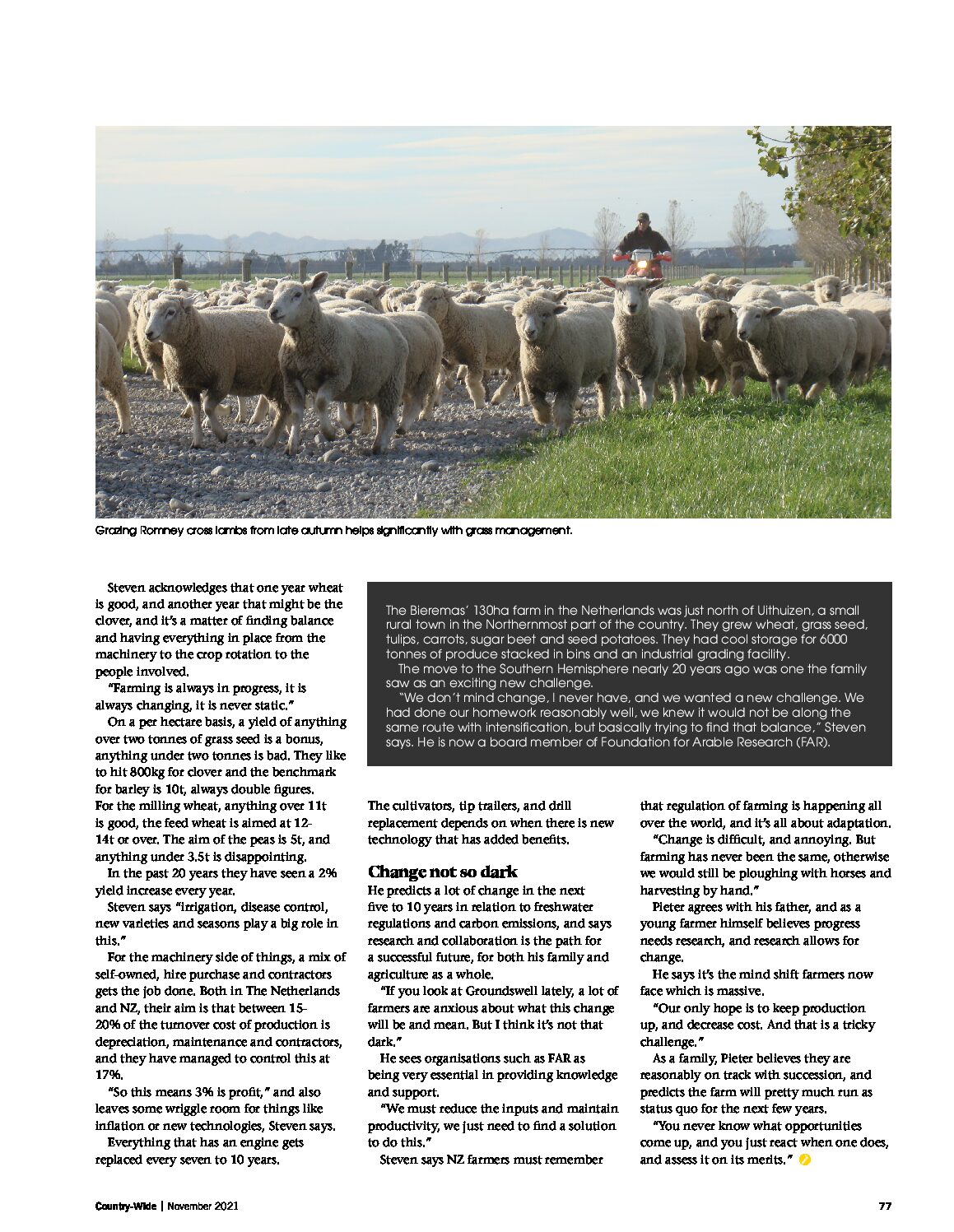

Autumn and spring cropping has always been on their annual programme. They feed lambs on the winter crops which change from clover to oats to new grass as grazing store lambs is a massive part of grass management. They prefer Romney cross lambs, which they buy later in the autumn, preferably store size between 30-33kg, and run an average of about 5000 in a season. Methods of drilling and cultivation can vary, the outcome dictates what they use. They try to find that middle ground with what works and what doesn’t work.

“The outcome is the goal, and how to get there is not a goal in itself.”

Autumn and spring-sown crops means finding a balance with the crop rotation, and different species means different modes of action for chemicals. On arrival in 2004, grass weeds were a problem, but diverse crop rotation and varying chemical use helped mitigate this; finding the middle ground and keeping everything in balance. Grass grub has been the biggest enemy, but there are still insecticides available to use and biologicals are looking to be a promising option for the future. “It will always remain a challenge,” Steven and Freda’s middle son Pieter Taco says. Incorporating all residues is done by cultivation. Wheat straw is sold to the mushroom industry. The waste product, mushroom compost, comes back to the farm and is used to increase the organic matter of the soil and therefore the fertility.

“Our goal is to make our farming system as circular as possible.”

They also lease two paddocks from their neighbours, which are on a 12-year rotation for potatoes and lilies. The lilies are grown for the bulbs, the potatoes for their seeds and processing. “A 12-year rotation means there is enough time to get the restorative phase back.” Pieter Taco, 26, has moved home to help run the farm. He studied Bachelor of Commerce majoring in agriculture at Lincoln University, has worked in Europe and Australia, and is now happy to be back on home turf with his parents. They do most of the work themselves including all the fertilising and spraying, a neighbour provides transport, and a contractor does the baling.

Succession a gradual process

Succession of the farm has always been an open conversation for the Bierema family, a gradual process both physically and mentally. “You are never solely the boss, you always have to deal with someone else,” Steven says, who bought his own family farm from his parents in The Netherlands and paid his three sisters out. “And we have to make sure we pass it on to the next generation in a good way.” The oldest son is a political scientist at Galway University (Ireland), while the youngest son works in the rural team for ANZ. Pieter is very aware of the changing regulations with farming such as freshwater, but is not overwhelmed or concerned.

“It’s baby steps every year, the farming world will not be turned on its head.”

Regulations set by the companies who buy their crops are a big part of their farm practice, but ones he acknowledges are for good reason, as it’s all about ensuring quality. The requirement for isolation blocks between different varieties of crops can prove difficult at times. It can be hard on their own farm and neighbouring farms. “Sometimes it’s up to five kilometres of isolation block. But you need that for quality standard.” Pieter says although not everything has to be sold prior to planting, you need those contracts, which are gained from proven track records.

“It’s about planning, and acknowledging that although not everything is successful, you learn as you go, and adjust as you go forward.”

Efficiency and simplicity with the different crops are the strengths of the farm, as are the good soils and irrigation which means good production security. The last five years has been about fine- tuning their methods, and they’ve added a grain drier and improved storage facilities. Steven says consistency is key, and the more control from their end, the more they are able to deliver. “Harvest time is crucial, so if the weather is not favourable, we can dry it ourselves.” Steven acknowledges that one year wheat is good, and another year that might be the clover, and it’s a matter of finding balance and having everything in place from the machinery to the crop rotation to the people involved.

“Farming is always in progress, it is always changing, it is never static.”

On a per hectare basis, a yield of anything over two tonnes of grass seed is a bonus, anything under two tonnes is bad. They like to hit 800kg for clover and the benchmark for barley is 10t, always double figures. For the milling wheat, anything over 11t is good, the feed wheat is aimed at 12- 14t or over. The aim of the peas is 5t, and anything under 3.5t is disappointing. In the past 20 years they have seen a 2% yield increase every year. Steven says “irrigation, disease control, new varieties and seasons play a big role in this.”

For the machinery side of things, a mix of self-owned, hire purchase and contractors gets the job done. Both in The Netherlands and NZ, their aim is that between 15- 20% of the turnover cost of production is depreciation, maintenance and contractors, and they have managed to control this at 17%. “So this means 3% is profit,” and also leaves some wriggle room for things like inflation or new technologies, Steven says. Everything that has an engine gets replaced every seven to 10 years. The cultivators, tip trailers, and drill replacement depends on when there is new technology that has added benefits.

Change not so dark

He predicts a lot of change in the next five to 10 years in relation to freshwater regulations and carbon emissions, and says research and collaboration is the path for a successful future, for both his family and agriculture as a whole. “If you look at Groundswell lately, a lot of farmers are anxious about what this change will be and mean. But I think it’s not that dark.” He sees organisations such as FAR as being very essential in providing knowledge and support.

“We must reduce the inputs and maintain productivity, we just need to find a solution to do this.”

Steven says NZ farmers must remember that regulation of farming is happening all over the world, and it’s all about adaptation. “Change is difficult, and annoying. But farming has never been the same, otherwise we would still be ploughing with horses and harvesting by hand.” Pieter agrees with his father, and as a young farmer himself believes progress needs research, and research allows for change. He says it’s the mind shift farmers now face which is massive. “Our only hope is to keep production up, and decrease cost. And that is a tricky challenge.”

As a family, Pieter believes they are reasonably on track with succession, and predicts the farm will pretty much run as status quo for the next few years. “You never know what opportunities come up, and you just react when one does, and assess it on its merits.” The Bieremas’ 130ha farm in the Netherlands was just north of Uithuizen, a small rural town in the Northernmost part of the country. They grew wheat, grass seed, tulips, carrots, sugar beet and seed potatoes. They had cool storage for 6000 tonnes of produce stacked in bins and an industrial grading facility. The move to the Southern Hemisphere nearly 20 years ago was one the family saw as an exciting new challenge.

“We don’t mind change, I never have, and we wanted a new challenge. We had done our homework reasonably well, we knew it would not be along the same route with intensification, but basically trying to find that balance,” Steven says. He is now a board member of Foundation for Arable Research (FAR).

See the article online here

Recent Comments