A family succession plan has seen a young couple establish their own farming operation in North Canterbury.

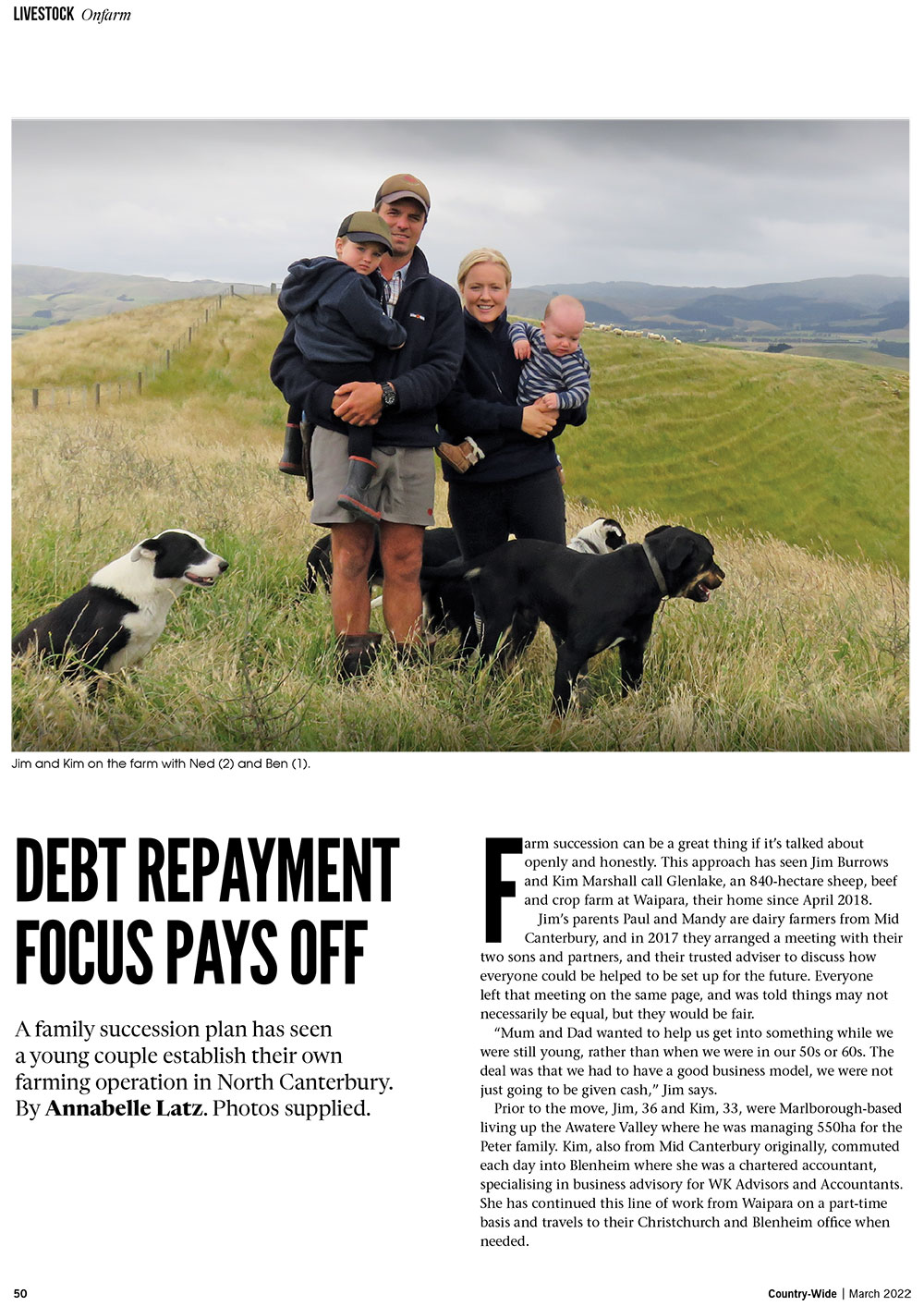

Farm succession can be a great thing if it’s talked about openly and honestly. This approach has seen Jim Burrows and Kim Marshall call Glenlake, an 840-hectare sheep, beef and crop farm at Waipara, their home since April 2018. Jim’s parents Paul and Mandy are dairy farmers from Mid Canterbury, and in 2017 they arranged a meeting with their two sons and partners, and their trusted adviser to discuss how everyone could be helped to be set up for the future. Everyone left that meeting on the same page, and was told things may not necessarily be equal, but they would be fair.

“Mum and Dad wanted to help us get into something while we were still young, rather than when we were in our 50s or 60s. The deal was that we had to have a good business model, we were not just going to be given cash,” Jim says.

Prior to the move, Jim, 36 and Kim, 33, were Marlborough-based living up the Awatere Valley where he was managing 550ha for the Peter family. Kim, also from Mid Canterbury originally, commuted each day into Blenheim where she was a chartered accountant, specialising in business advisory for WK Advisors and Accountants. She has continued this line of work from Waipara on a part-time basis and travels to their Christchurch and Blenheim office when needed.

About 12 years ago Jim and Kim did start to plan for the future financially, even if they weren’t sure what the exact picture would be. They bought 50 dairy cows and leased them to Jim’s parents. The lease was a replacement heifer for every three cows, which grew to 100 cows plus every other age group. “That started the capital, we then started selling age-group heifers. We also bought grazing lambs to put in the vineyards around Marlborough.” Life was busy, juggling these side hustles alongside his full time manager position, but it did feel good putting some extra funds away for the future. Jim admits he had become resigned to the fact he may have to be a manager perhaps forever, because climbing the rung of the ladder to farm ownership often seemed a financial impossibility. His parents were dairy farmers, and he had no interest in following in their footsteps.

“They had watched Kim and I build our personal assets over the previous eight years, and I remember mum saying ‘we knew you were so ready,” which is when they brought us all together to talk about succession.”

Pushing the go button

High country farming is where Jim’s heart truly lies, but this farm in North Canterbury was too good not to consider, even though Kim thought it would be well out of their price range. “The agent talked us into ‘looking at it,’” she says. Jim says it was also down to timing – everyone was coming out of rough times with the Global Financial Crisis and the farm had been on the market a few years. North Canterbury had been through a prolonged drought, the owners finally wanted out, and with that, their offer was accepted. So with this rolling hill farm a realistic possibility, the go button was pushed. They cashed up the stock they were leasing out. With those funds, a loan from the bank, and from Mandy and Paul, they managed to buy their own farm and stock. The young couple had never had debt before this, believing in the philosophy that if they didn’t have the cash, they didn’t need it. “Having debt with that many zeros on the end of it almost didn’t seem real, but we were excited to start building our future,” Jim says.

Having their own place to invest in and run to the best of its capabilities was the best feeling, and with Kim’s financial skills, they could not have been happier. “It felt like home from the first night,” Kim says. They were not prepared to just go out and buy ewes for capital stock during their first winter there with the risk of value drop, so opted for dairy grazing and fattening lambs and store cattle to generate income without out laying more capital. That first winter was tough, and Kim was also commuting to Blenheim fairly often for her job. They were break-fencing 1100 cattle and grazing 3000 mixed-breed lambs to start them off.

“I’d be shifting 15 breaks a day, often by head torch, but it was worth it,” Jim says.

Jim and Kim agree their financial performance for the past three years has been good, with their gross farm income (GFI) about $1276/ha and $171/su. “We have been very financially focused, paying down debt when we can, or leveraging against our equity to invest in other opportunities. This is still a very big focus for us, however work/life balance is definitely something we still need to work on… one day,” Kim says. They made a point of running as lean as they could when they did start to buy capital stock, waiting 12 months before employing a casual worker one to two days a week. This meant they had the stock paid off in the first six months. Running lean included using contractors instead of buying machinery which meant the best person doing the job, minimal capital costs and repairs and maintenance. Careful spending for everyday items also played a big part. Their lean approach reflected in their ability to repay the debt, which in turn kept the bank happy, Kim says.

This worked in their favour particularly a year after being on the farm when the neighbours’ 170ha farm came up for sale. It was their goal to add more scope to the farm, but this premature opportunity was too good to turn down. “We thought this property might come up for sale in the next five years, not one. However, the bank was very supportive in helping us fund the next property, as we had proven we could be very aggressive with our debt repayments,” Kim says. They’ve since approached the bank again, to lend against their equity to mobilise funds they can invest.

“You’ve got to leverage what you’ve got and make your money work by investing it.

The bank sells you money

“The bank’s job is to sell you money, not look after it – when inflation is over 5% and bank interest is 0.5%, you’re pretty much going backwards if you have money sitting in savings doing nothing,” Jim says. In 2019 they ran their farm working expenses at 45%, 2020 was 42%, and 37% in 2021. “Most farmers sit over 50%, so we’re doing pretty well for this country,” Jim says. Their first son Ned was born in November 2019, Ben just over a year later in January 2021. Glenlake is early warm, healthy country, lambing in late July. Great fertility means they can focus on growing quality legumes, particularly lucerne, sub clover and if they happen to get some summer rain red and white clovers.

“When we arrived four years ago the farm had been used for service bulls and there hadn’t been a sheep on it for 10 years,” Jim says.

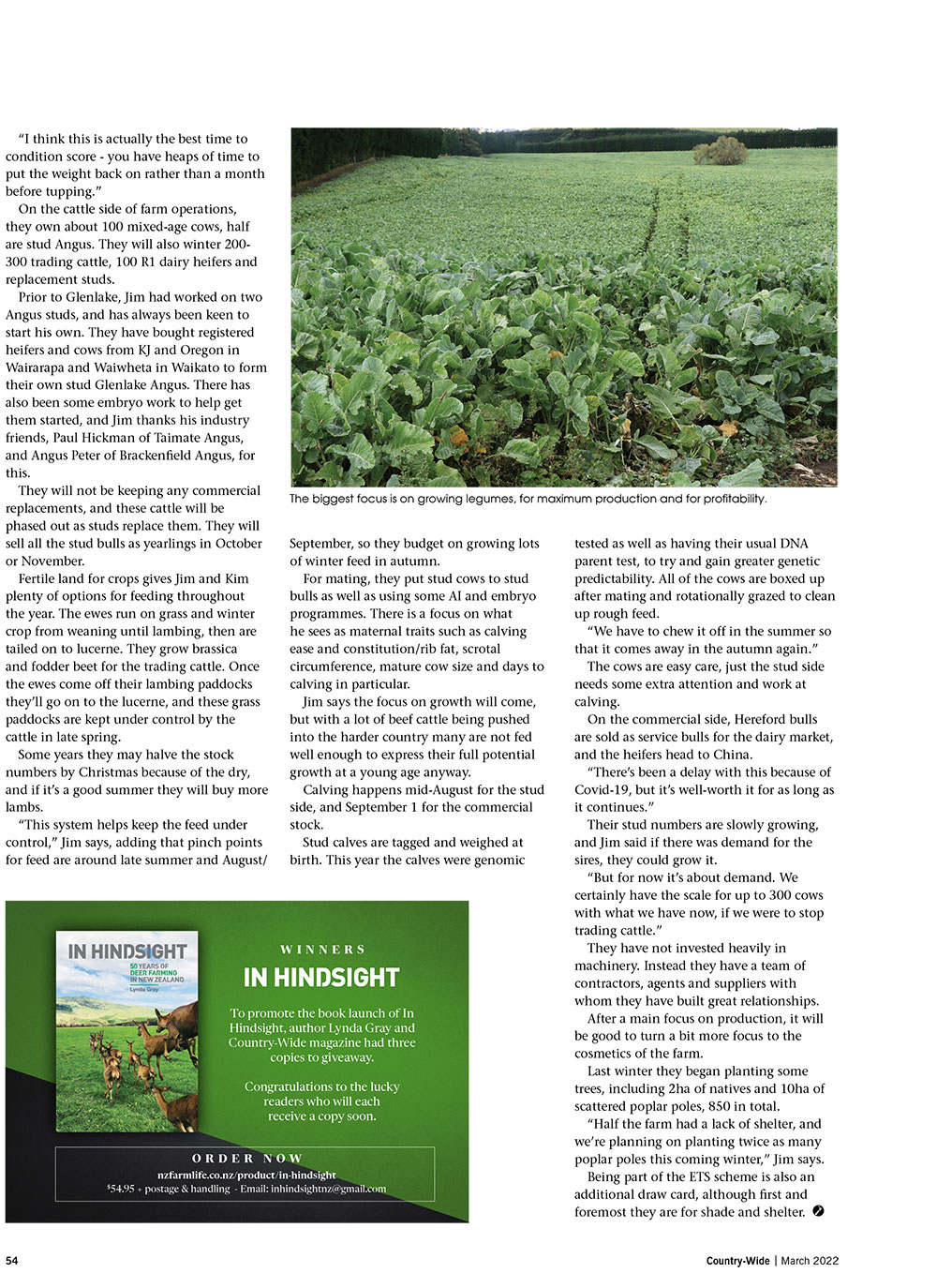

The first priority was fencing and replacing any small troughs with 750-litre troughs to increase water reliability. Anything Jim could get a tractor over that was growing browntop has been replaced with lucerne, herb and clover mixes, a tetraploid ryegrass and some permanent ryegrass mixes. He has sown another 30ha of lucerne this season, with 90ha already in the ground. “Our biggest focus is on growing legumes, for maximum production and for profitability.” Everything flatter, north facing or the drier paddocks is in lucerne but for grazing rather than balage. This does come with its challenges like stock deaths for ewes because of lack of fibre and subsequent gut problems. Jim admits it’s good bloat country too, with the lush short spring seasons. Clover and chicory make up 45ha of the farm which the hoggets are grazed on with lambs at foot until weaning, resulting in good production.

Looking around the farm this summer, it’s lush and the stock are thriving. But they have had some very hard lessons along the way too. The first year at Glenlake plenty of rain fell, so they bought 300 yearling bulls on top of all the trading stock already on, predicting plenty of growth. Then the worst thing that could happen, happened. “We had a dry autumn, and that is the biggest killer,” Jim says. Being caught short on feed and water made him grateful it was bulls he had, not steers. They managed to get through, but it was a good reminder that in North Canterbury you’re never too far away from a drought.

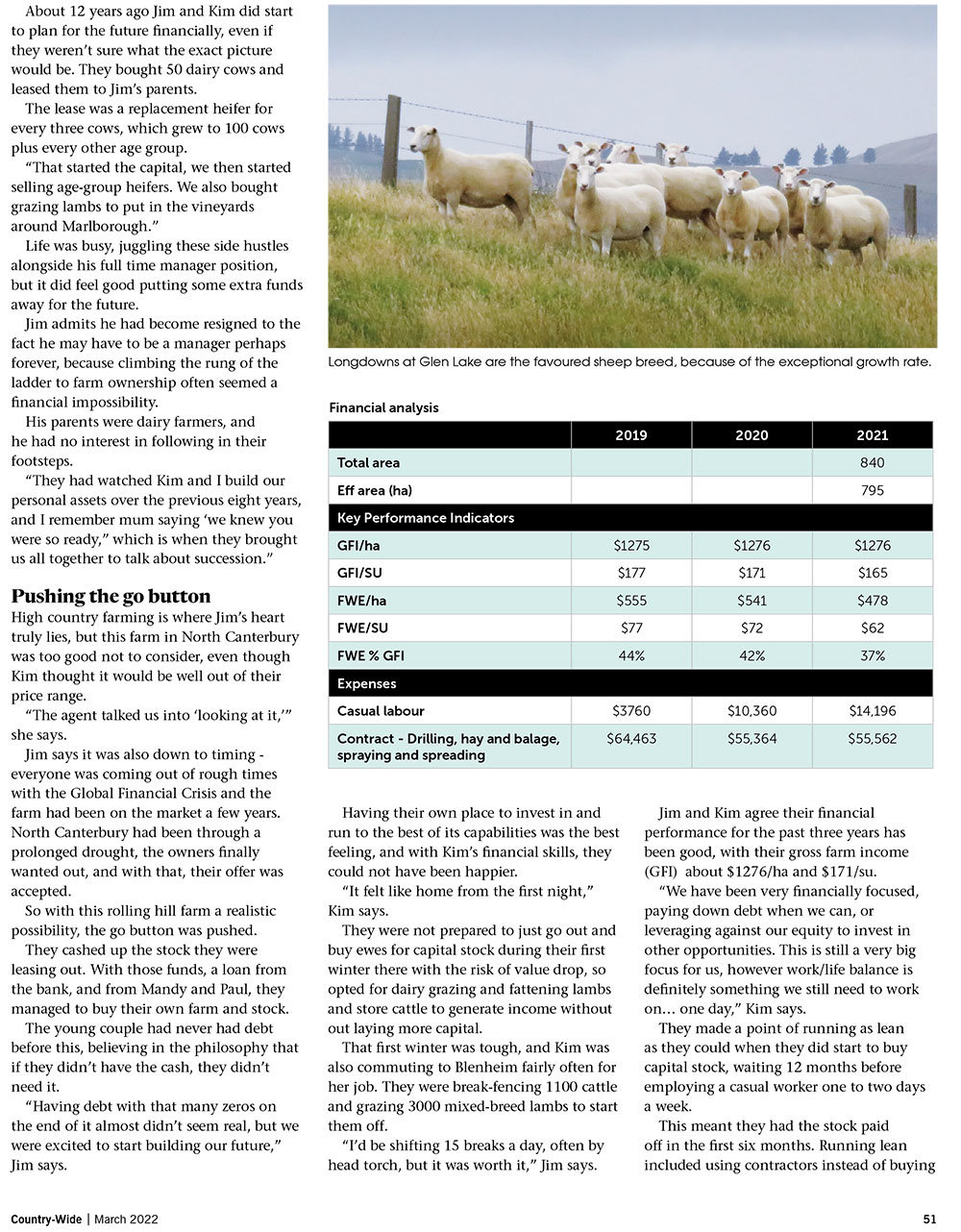

Buying capital stock was something Jim and Kim did not rush into, their philosophy being that capital stock is a long-term game, as once it’s paid off, it’s all profit and less working expenses. “It’s all about timing,” Jim says. On the farm they have 1500 maternal ewes that lamb about 148%. They will buy in 1000 one-year-old ewes this year in January to mate to Polled Dorset rams. There are 500-700 hoggets, which have scanned at 127% for the last two years and weaning 95%. Longdowns are the maternal breed of choice because of their exceptional growth rate along with great fertility. The average weaning weight is about 38kg, with the hogget lambs about 33kg.

Snow could not have fallen at a worse time last winter, with it being mid-lambing season, their lambing subsequently dropping by 12%. “If I’d age-scanned into tighter groups I’d have been able to prioritise shelter,” Jim says, adding that having your own farm is one big constant learning curve. The rams go out about February 25, with the plan to wean on November 15. “Normally 70% of the lambs are off to slaughter, aiming to kill at 20kg off their mum in the first draft. We keep the weights pretty high, aiming for 21kg post-weaning.” Longdowns aren’t flushed, and scan at about 175-180%, without looking for triplets.

Every three weeks after weaning they will draft more for slaughter. From November store lambs are bought, and over the summer there’ll be about 4000 which are fattened to 21kg and then sold off again. They shear every six months and usually break even on the ewe wool. They don’t drench the ewes, but because they’re fed so well there is very little pressure on them.

A dabble with Merinos

They’ve dabbled with a few fine-wool breeds like a Merino over Longdown hoggets, but they just weren’t achieving the desired lambing percentages or growth. Kim says Jim’s strength is being adaptive, looking for opportunities, and having not come from a sheep and beef family, he has no set tradition to follow. “We aim for a minimum return of 20c/ kg drymatter on trading stock and often do twice that, and it’s what we balance our business decisions on,” Jim says. The replacement lambs and ewes are shorn at weaning, and the ewes condition scored.

“I think this is actually the best time to condition score – you have heaps of time to put the weight back on rather than a month before tupping.”

On the cattle side of farm operations, they own about 100 mixed-age cows, half are stud Angus. They will also winter 200- 300 trading cattle, 100 R1 dairy heifers and replacement studs. Prior to Glenlake, Jim had worked on two Angus studs, and has always been keen to start his own. They have bought registered heifers and cows from KJ and Oregon in Wairarapa and Waiwheta in Waikato to form their own stud Glenlake Angus. There has also been some embryo work to help get them started, and Jim thanks his industry friends, Paul Hickman of Taimate Angus, and Angus Peter of Brackenfield Angus, for this.

They will not be keeping any commercial replacements, and these cattle will be phased out as studs replace them. They will sell all the stud bulls as yearlings in October or November. Fertile land for crops gives Jim and Kim plenty of options for feeding throughout the year. The ewes run on grass and winter crop from weaning until lambing, then are tailed on to lucerne. They grow brassica and fodder beet for the trading cattle. Once the ewes come off their lambing paddocks they’ll go on to the lucerne, and these grass paddocks are kept under control by the cattle in late spring. Some years they may halve the stock numbers by Christmas because of the dry, and if it’s a good summer they will buy more lambs.

“This system helps keep the feed under control,” Jim says, adding that pinch points for feed are around late summer and August/September, so they budget on growing lots of winter feed in autumn. For mating, they put stud cows to stud bulls as well as using some AI and embryo programmes. There is a focus on what he sees as maternal traits such as calving ease and constitution/rib fat, scrotal circumference, mature cow size and days to calving in particular. Jim says the focus on growth will come, but with a lot of beef cattle being pushed into the harder country many are not fed well enough to express their full potential growth at a young age anyway. Calving happens mid-August for the stud side, and September 1 for the commercial stock. Stud calves are tagged and weighed at birth. This year the calves were genomic tested as well as having their usual DNA parent test, to try and gain greater genetic predictability. All of the cows are boxed up after mating and rotationally grazed to clean up rough feed. “We have to chew it off in the summer so that it comes away in the autumn again.”

The cows are easy care, just the stud side needs some extra attention and work at calving. On the commercial side, Hereford bulls are sold as service bulls for the dairy market, and the heifers head to China. “There’s been a delay with this because of Covid-19, but it’s well-worth it for as long as it continues.” Their stud numbers are slowly growing, and Jim said if there was demand for the sires, they could grow it. “But for now it’s about demand. We certainly have the scale for up to 300 cows with what we have now, if we were to stop trading cattle.” They have not invested heavily in machinery. Instead they have a team of contractors, agents and suppliers with whom they have built great relationships. After a main focus on production, it will be good to turn a bit more focus to the cosmetics of the farm. Last winter they began planting some trees, including 2ha of natives and 10ha of scattered poplar poles, 850 in total.

“Half the farm had a lack of shelter, and we’re planning on planting twice as many poplar poles this coming winter,” Jim says.

Being part of the ETS scheme is also an additional draw card, although first and foremost they are for shade and shelter.

Recent Comments