IKEA Shifting Into Carbon Forestry? New Zealand

Country Wide Magazine, May 2022

The company behind multi-national furniture and home accessories brand IKEA claims its purchase of a large Southland farm is for production forestry, not carbon farming, Annabelle Latz reports. An international company which recently bought Wisp Hill Station in Southland claims its objective is, first and foremost, to create a production forest, not to mine carbon. This is despite the fact the company is in the process of registering with the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS). The 5500ha sheep and beef farm is the first land bought in New Zealand for Ingka Investments, the investment arm of the group and its retail business IKEA.

The purchase agreement became unconditional with the approval of land acquisition by the Overseas Investment Office on Friday, August 27, last year, bought from the Ward family. A lease- back requirement will allow the family to properly phase out their operations over a minimum three-year period. Country-Wide was refused a verbal interview with Ingka Investments, and received written statements instead.

Ingka’s forestland investments portfolio manager of Andriy Hrytsyuk said the plan is to grow a productive forest within an afforestation project which expands its global forestry portfolio and demonstrates its commitment to responsible forest management, with a focus on timber sales to generate a return on investment.

This recent conversation with Ingka Investments was the result of the cover story in Country-Wide’s March issue, Carbon Mining Exposed which stated the neighbouring 1250ha of Southland farm of Logan Evans called Koneburn had been bought by an international company for carbon mining, some 80km from Wisp Hill Station. Country-Wide did not mention the name of the buyer. Ingka Investments contacted Country- Wide directly, specifically referencing Wisp Hill Station but not the farm mentioned in the article.

Two farms bought

Country-Wide understands Ingka Investments has bought at least two farms in Southland on which they plan to plant both pine and native trees, one of them being Koneburn, the ownership being transferred to them on June 30, 2022.

Writing specifically about Wisp Hill Station, Hrytsyuk claimed it will not be a carbon farm, and stated carbon credits will not be part of the calculus. “They are not sold, nor we do not engage in internal carbon offsetting to reduce our carbon footprint.”

In a media release last September, Ingka Investments stated it will be planting 330ha in radiata pine seedlings, with a long term plan to have a total of 3000ha and more than three million seedlings, planted in the next five years. At the same time the plan is to naturally regenerate the remaining 2200ha into native bush. The new forestry investment in NZ will see its forest planned harvest take place at the end of the first rotation, 29 years after planting.

“Our plans include serious investment into native species enhancement, and all the main riparian areas are earmarked to be planted in native species including manuka. A significant gorse and weed control programme has already been implemented on these riparian areas, something that has lacked any investment for over 50 years on the property.”

Hrytsyuk told Country-Wide in March that Ingka Investment’s afforestation business

is a long-term investment which focuses on the cycle of planting seedlings on unforested land that will eventually become mature trees for harvest.

“We have begun the process of registering the property with ETS because it was the logical, prudent step to take as newcomers to the New Zealand market, but again we have no intention of selling carbon credits,” he said, adding that they will calculate and report the amount of carbon removed and stored in the trees, both in NZ and other countries.

It is Ingka Investments’ plan to draw on labour units to develop and eventually harvest the trees, and invest in native species enhancement. Hrytsyuk said the property will require years of labour inputs including preparing the soil, planting the seedlings, pest and weed control, thinnings and more, before harvest can happen.

Hrytsyuk acknowledged NZ’s proud tradition of agriculture, and the importance of its role in the economy, but added “forestry also has a role to play”.

“Our approach to responsibly manage forestry provides jobs and economic growth on the same land while also making a positive impact on the climate through carbon sequestration and biodiversity.”

All wood harvested in their forests is sold on the open market and does not comprise a significant part of the IKEA supply chain, (as a home furnishings retailer).

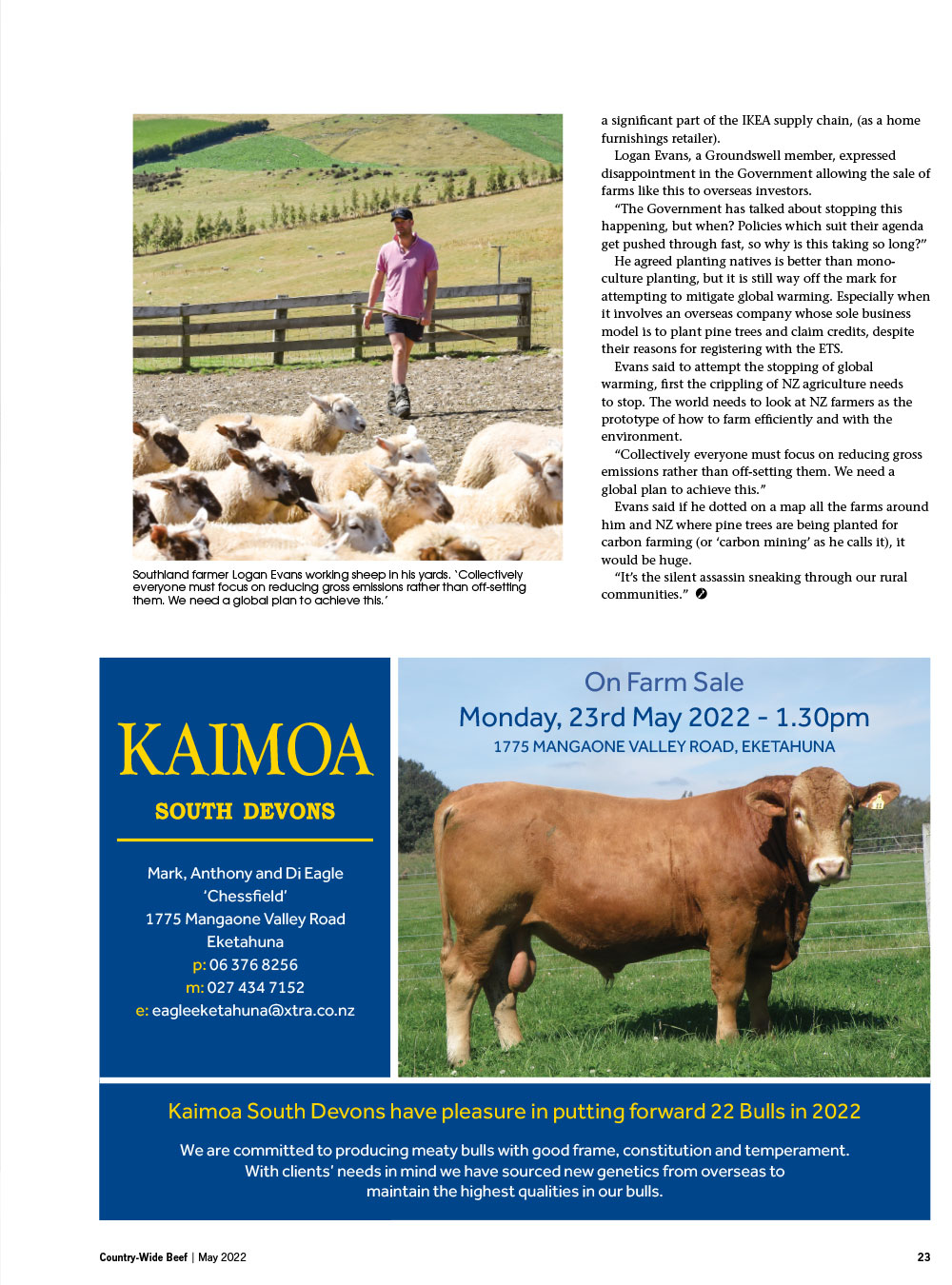

Logan Evans, a Groundswell member, expressed disappointment in the Government allowing the sale of farms like this to overseas investors.

“The Government has talked about stopping this happening, but when? Policies which suit their agenda get pushed through fast, so why is this taking so long?”

He agreed planting natives is better than mono- culture planting, but it is still way off the mark for attempting to mitigate global warming. Especially when it involves an overseas company whose sole business model is to plant pine trees and claim credits, despite their reasons for registering with the ETS.

Evans said to attempt the stopping of global warming, first the crippling of NZ agriculture needs to stop. The world needs to look at NZ farmers as the prototype of how to farm efficiently and with the environment.

“Collectively everyone must focus on reducing gross emissions rather than off-setting them. We need a global plan to achieve this.”

Evans said if he dotted on a map all the farms around him and NZ where pine trees are being planted for carbon farming (or ‘carbon mining’ as he calls it), it would be huge.

“It’s the silent assassin sneaking through our rural communities.”

See the article online here

Recent Comments