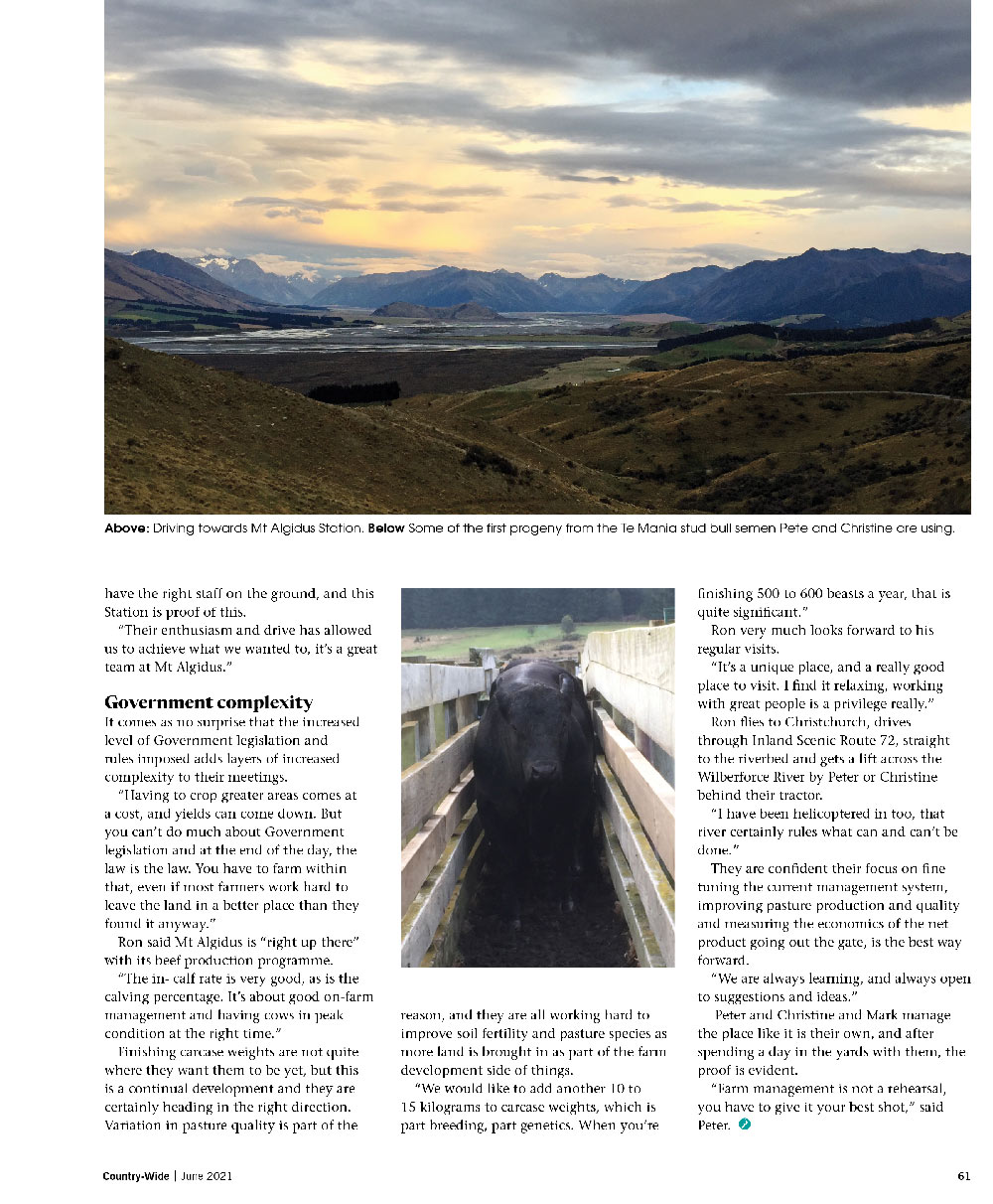

A river running through Mt Algidus Station is just one of the challenges faced by station managers Peter and Christine Angland. Story and photos by Annabelle Latz.

It is unruly and has no manners at all. Life at Mt Algidus Station is heavily governed by the Wilberforce River, so going home chariot style is everyday living for station managers Peter and Christine Angland. They took the helm of the 22130ha beef and sheep high country property in 2012, accepting the immediate fact that they cross the Wilberforce River only when it chooses for them to do so. Mt Algidus Station sits at the foot of the Main Divide in Canterbury, where the Mathias, Rakaia and Wilberforce Rivers meet. As the crow flies, from their house Peter and Christine are actually closer to the West Coast’s Hokitika than Christchurch. The couple had made the move north from Waipori Station in Otago, which they’d been managing for 14 years. Previously they’d been managing Half Way Bay Station on the shores of Lake Wakatipu for six years, and Peter was working on nearby Mt Nicholas Station for six years before that.

‘Everything comes down to the weather here – there is a lot of peering at weather maps to decide when various things are going to happen – getting contractors, stock, supplies and visitors in and out all depends on being able to cross the river,” said Christine, while setting up for a day of TB testing in four different yards across the flats. They have three children who are cutting their own futures in various industries; Lachie, 27, works in cropping on arable land near Rakaia, Campbell, 26, has just joined the navy as a pilot and Annabel, 25, works in viticulture at Peregrine Wines. Peter and Christine had visited the area several times before moving to Mt Algidus, previously picking rams at nearby Snowden Station. The area with its massive landscape and history struck a chord, so when the opportunity to manage it arose, they went for it.

“The potential this place has is huge.”

Full time assistant manager Mark Pilcher is a key part of the team with his huge range of skills. He comes from a varied farming background including outback Australia and dairy farming, but has embraced the high country way of life. Beef production has been a major focus, all keeping their eye solidly on their goal of breeding efficient cows. They currently calve 1300 cows including 2 year-old calvers, and winter 2680 cattle in total, after selling mainly annual draft and finished 18-month-old cattle with some stores recently with the change in TB status.

“Our tail end 18 month old cattle stay another winter to help with tidying up poorer quality pasture in the summer.” Predominately the Anglands breed straight Angus cattle, with some Charolais and Hereford bulls in the mix to add some hybrid vigour going over the less desirable cows.

DNA technology

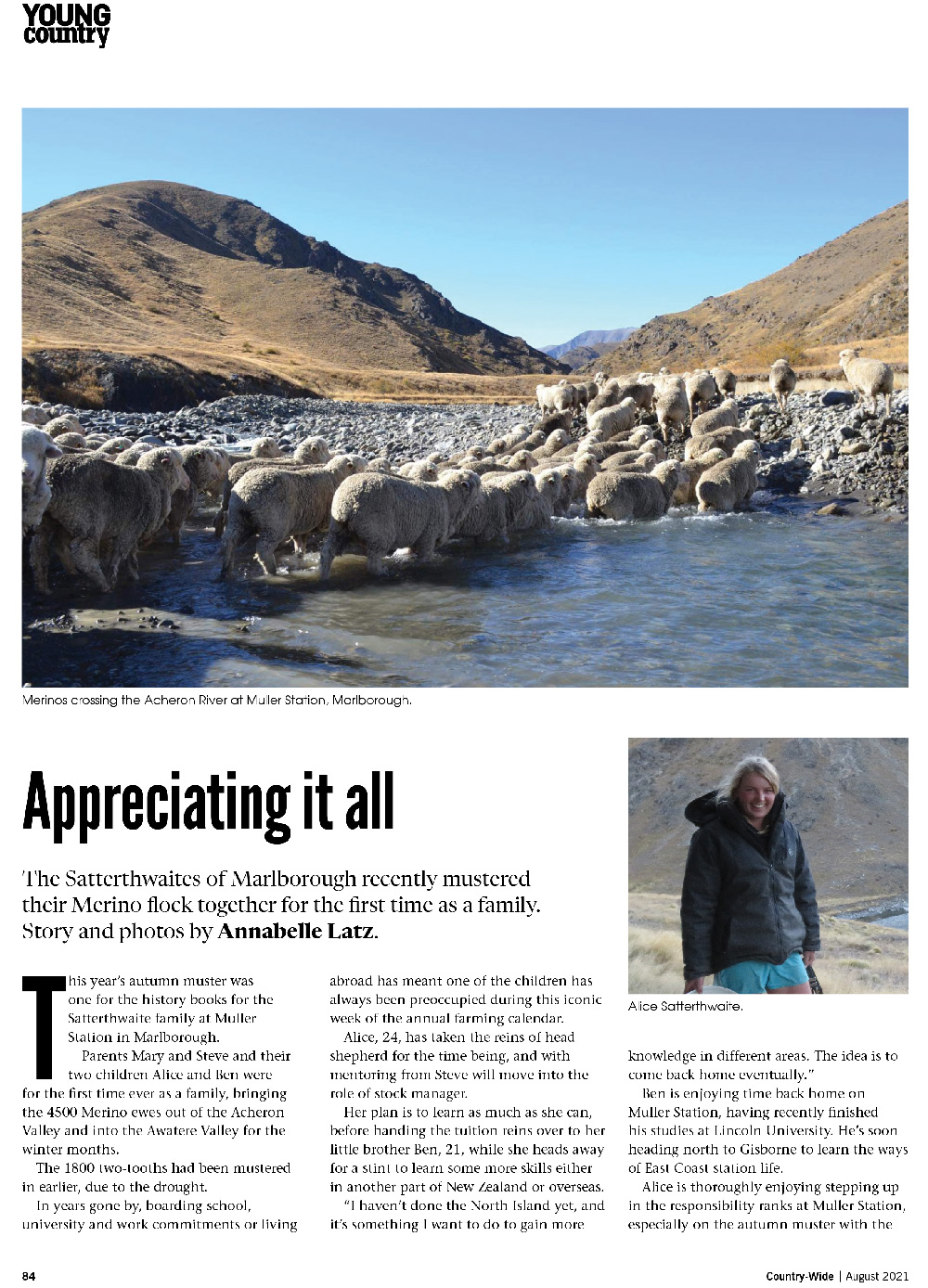

Peter said DNA technology will be a huge benefit for them achieving their breeding goals for the future improvement of the herd. All their heifers are home bred, and as the DNA records build it will be great help for making informed breeding decisions. “We can now use the estimated breeding values (EBVs) for the heifers to match to the bulls to improve their indicated weaknesses. In the next five to six years we will have a DNA profile on most of our cows, including both hybrid and purebred stock. That is pretty exciting,” said Peter. For the Anglands, breeding an efficient cow means calves that are not too big at birth, cows that are fertile, moderate sized with positive fats. Good 600kg Day Weights and intramuscular fat are now also being brought into the mix to improve carcase quality and size without hopefully increasing cow size too much. They have started breeding their own bulls using semen straws from Te Mania Angus stud, and really like what they are seeing with the offspring.

“Breeding and DNA testing our own heifers costs no more than buying a team of 12 or so bulls which we were needing to do each year and gives us access to better bulls than we could otherwise afford . DNA data can be a very useful tool and compliment progeny testing. It is just another tool to use when making breeding decisions.”

Sheep are another component at Mt Algidus. When the Anglands arrived 12 years ago most of the sheep had just been sold with only 260 MA ewes and 600 ewe hoggets remaining. This had been done due to a TB outbreak and not being able to sell store cattle as had been the practice so something had to give for feed reasons. The property has just completed its fourth clear whole herd test. Sheep numbers have been built up again to help with pasture management and weed control, and ewe numbers are slowly rising with ewe lambs retained as replacements and the balance of lambs mostly finished. The Anglands’ farm 3800 sheep, mainly Perendale ewes, mating the hoggets to Dorper crosses.

“This has led to easy lambing in the hoggets and the lambs grow and yield well,” said Christine.

Anything showing any sign of feet problems is managed with trimming and footbathing then mated to a Texel Suffolk cross ram for the rest of their time on the Station. Mt Algidus on average receives 1180mm of rain per year, with the Main Divide just behind them receiving as much as six metres.

“One December, there was one metre of rain in five days at Browning Pass on the Divide,” said Peter.

The high country farming scene has certainly seen some shifts over the years, with proposed changes in Government legislation and local body plans.

“It’s a matter of finding a happy medium, finding a way to work together and making science-based decisions.”

He and Christine have worked out their own refined grazing and pasture renewal programme. Generally it was swedes, followed by kale, then sowing back to pasture on the more productive country. Now, with the proposed slope and resowing “rules” in regards to winter cropping, some winter crops are being grown out in the stonier flatter areas of the farm which means more crop needs to be grown as the yields are not as good on this soil type. Rape and turnips are being autumn sown in these areas as this class of land is summer dry. Fencing off waterways with gravity fed stock water systems from mountain streams has been part of the great synergy they work hard on.

There are also five QEII Reserves at Mt Algidus, which help maintain the special vegetation pockets, with two more in the pipeline. Ron Halford is another pivotal name within the essential working cogs at Mt Algidus Station. The Otaki-based farm adviser has been helping pave the way of high country farming success here for a decade. He already knew the area well, as had been farm advisor on nearby Lake Coleridge Station and Acheron Bank Station, for Bruce Miles. Ron visits the Station every two to three months, spending a couple of days with Peter and Christine as they collectively talk about the issues of the day, discuss the next quarter, review the financials, and make any required adjustments, to make those bottom line profits. When he first joined the ranks at Mt Algidus, there was a big focus on increasing cattle numbers and reducing sheep numbers, and over time increasing sheep numbers again. The big goals have remained the same, including managing water, increasing cattle numbers by building up a sufficient breeding herd, and looking after the environment in the form of retiring land when required, and fencing off significant waterways and land areas of significant conservation value. Ron said it is absolutely important to have the right staff on the ground, and this Station is proof of this.

“Their enthusiasm and drive has allowed us to achieve what we wanted to, it’s a great team at Mt Algidus.”

Government complexity

It comes as no surprise that the increased level of Government legislation and rules imposed adds layers of increased complexity to their meetings. “Having to crop greater areas comes at a cost, and yields can come down. But you can’t do much about Government legislation and at the end of the day, the law is the law. You have to farm within that, even if most farmers work hard to leave the land in a better place than they found it anyway.” Ron said Mt Algidus is “right up there” with its beef production programme. “The in-calf rate is very good, as is the calving percentage. It’s about good on-farm management and having cows in peak condition at the right time.” Finishing carcase weights are not quite where they want them to be yet, but this is a continual development and they are certainly heading in the right direction. Variation in pasture quality is part of the reason, and they are all working hard to improve soil fertility and pasture species as more land is brought in as part of the farm development side of things.

“We would like to add another 10 to 15 kilograms to carcase weights, which is part breeding, part genetics. When you’re finishing 500 to 600 beasts a year, that is quite significant.”

Ron very much looks forward to his regular visits. “It’s a unique place, and a really good place to visit. I find it relaxing, working with great people is a privilege really.” Ron flies to Christchurch, drives through Inland Scenic Route 72, straight to the riverbed and gets a lift across the Wilberforce River by Peter or Christine behind their tractor. “I have been helicoptered in too, that river certainly rules what can and can’t be done.” They are confident their focus on fine tuning the current management system, improving pasture production and quality and measuring the economics of the net product going out the gate, is the best way forward.

“We are always learning, and always open to suggestions and ideas.”

Peter and Christine and Mark manage the place like it is their own, and after spending a day in the yards with them, the proof is evident.

“Farm management is not a rehearsal, you have to give it your best shot,” said Peter.

Recent Comments